In today’s journalism, where different storytelling mediums have come together, it is worth taking a second look at the many graphic novels that now populate bookstore shelves.

In today’s journalism, where different storytelling mediums have come together, it is worth taking a second look at the many graphic novels that now populate bookstore shelves.

Graphic novels, what some consider glorified comic books or “sequential art,” have increasingly become appreciated as a distinct, often touching art form. However, it can also serve as a source of inspiration in our storytelling, particularly online. Take Slate‘s recent presentation of the Sept. 11 Commission’s report in the form of an online graphic novel. Some may argue this is entertainment in the vein of a Hollywood film like World Trade Center.

But take a closer look. The graphic novel is well-researched and adheres tightly to the commission’s report. Instead of a writer interpreting the story, in this case, we have a writer AND an artist. Isn’t this similar to a news graphic, which also explains something or tells a story? This is clearly a form of unique journalism that merits further exploration.

As many multimedia journalists will attest, what is new about the Web as a medium for journalism is the ability to control time. Like a newspaper, one can let a reader control the speed at which he consumes the information. Or, one can do it for him, as do television journalists. The Web offers both.

When I create an audio slideshow, write a story or create a Flash package, I often look to comic books a source of inspiration for storytelling techniques. Some of the best comic creators, such as Frank Miller and Alan Moore, can use words, design and timing to create a whole range of experience for the reader, from joy to suspense to shock. These techniques can be translated as which images are used in that slideshow, how one edits the audio and even how long a particular image is displayed.

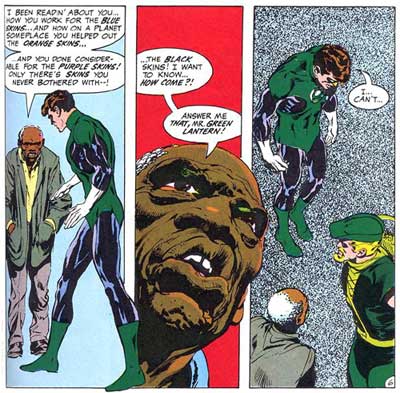

Let’s take for instance these famous panels by Neal Adams from a Green Lantern/Green Arrow story published by DC Comics in the 1970s, a time when this particular comic book was exploring social issues such as racism and corporate greed:

For another interesting example, take this scene by Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely from Marvel’s New X-Men, where an enemy is threatening to take over Professor Xavier’s mind and use it for evil purposes. Xavier responds to the attack by threatening to kill himself.

Surely not a scene one would encounter covering a city commission meeting, but think about the basic elements in the panels. It is a man sitting in a chair; he is angry, and he is holding an object.

What compels us about this scene, aside from the death threat, is the focus on individual aspects that make us take notice: the bloody nose, the enemy’s lips, the gun being drawn. Using similar “camera” angles and timing, imagine this is an angry resident at a city commission meeting gripping a microphone. Or, it could be the city commissioners themselves contemplating legislation while compelling audio is playing. This could be a pen at a bill signing or a poll worker handing out a ballot.

Take a look at this audio slideshow by the Sun-Sentinel that uses many of these comic book-like techniques. While I can’t say whether the editors are comic book fans, they do use timing, motion and detail in this presentation to creatively engage a reader in what is actually a very simple scene.

For anyone interested in exploring comics as a medium, I would highly suggest purchasing a copy of Scott McCloud’s’ Understanding Comics. This primer, told in comic book form, is arguably the best book on comics ever written and has various sections on timing for effect. For actual graphic novels that employ some excellent cinematic techniques, check out Watchmen by Alan Moore and Sin City by Frank Miller.

Oh, and don’t get caught reading that fluff around the newsroom either…